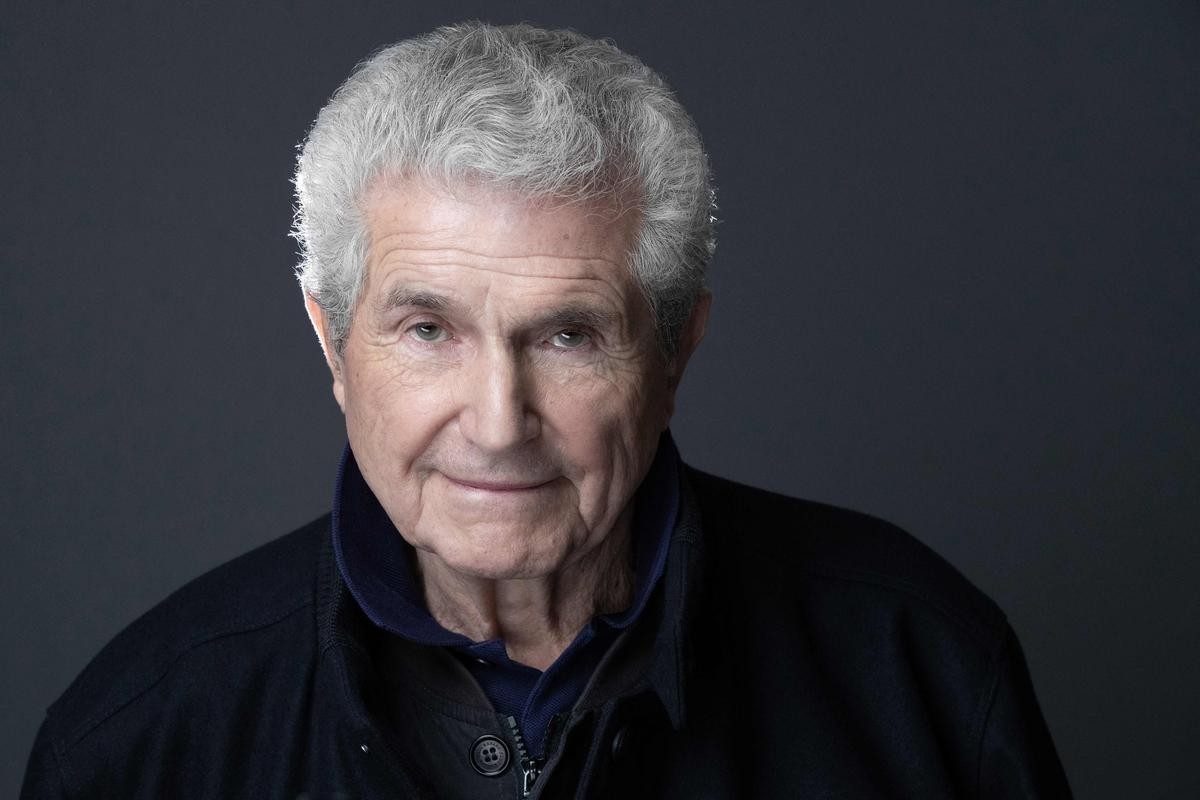

【2024 KFF Report】Masterclass of the "French OZU" – Claude SAUTET A Mature, Restrained, and Honest Commercial Filmmaker

|

|

Words by CHEN Chieh-yao (Independent scholar)

This year marks the centenary of the low-key yet highly successful middle-class French filmmaker Claude SAUTET, aptly dubbed the "French OZU" for his enduring aesthetic contributions to world cinema. Like Japanese filmmaker OZU Yasujirō, SAUTET honed his mature and restrained style at traditional studios, producing crowd-pleasing works that convey the bittersweet essence of ordinary life.

Both were renowned for their focus on the common people, and even shared similarities in their approach, such as living with screenwriters for months to turn daily conversations and observations into films. Both were known for demanding precise body movements and dialogue delivery, and films that captured the pulse of society, with OZU portraying Japan’s post-war societal shifts, and SAUTET reflecting on the post-1968 liberation of women and vulnerability of men.

A Filmmaker Refined by the Studio System

Even seasoned cinephiles assume that SAUTET was a middle-class director who inherited studio traditions and opposed the French New Wave's street style. But this perhaps requires more consideration, as SAUTET was a former Communist who shared mutual respect with New Wave directors.

While most New Wave directors started off as intellectual f ilm critics, SAUTET failed his university entrance exams and avoided Nazi conscription by enrolling in film school, allowing him to work at a studio after the war.

Like many filmmakers at the time, he joined the Communist Party (but later left due to disillusionment with Stalinist dogma). As the New Wave took place outside the studios, SAUTET refined his craft in studios for over a decade before directing his first feature in 1960, a crime film starring Jean-Paul BELMONDO.

However, both of SAUTET’s films in the 1960s were commercial and critical failures. SAUTET’s breakthrough came with 1970’s The Things of Life, which marked his shift to social realism romance films, kicking off one box office hit after another and numerous award wins.

Despite his studio roots, SAUTET's successful commercial film model cannot be deemed "anti-New Wave." Although he operated outside the New Wave, he was about 10 years older than the Cahiers du Cinéma critics-turned-directors, and also rose to fame a decade later. He shared a close bond with these directors, including François TRUFFAUT, who introduced him to script doctoring, facilitating his transition from screenwriting to directing.

Pursuing Cinematic Restraint and Musicality

Musicality defined SAUTET's social realism films, imbuing his seemingly issue-driven stories with a core emotional flow. He once said that film is a kind of music with its own rhythm, timing, and internal movement structure.

SAUTET eventually stopped chasing plot or action to seek musicality, aiming for magical moments where "force and harmony unfold together" to achieve a "complete and intense" emotional f low. SAUTET's pursuit of musicality is most evident in A Heart in Winter, in which Maurice RAVEL’s mournful strings echo the intense emotional interplay of the characters.

Honest Perspective on Women's Liberation and Men’s Vulnerability

The impression that SAUTET’s films reflect the middle-class male perspective perhaps requires scrutiny. A crucial aspect of his films is honesty — reflecting his personal journey from suburban working class to urban gentry, as well as his perspective on the liberation of women post-1968 protests and the vulnerability that men can finally display.

These themes were explored in the five films SAUTET made with actress Romy SCHNEIDER. In their final collaboration, centered on abortion, SCHNEIDER played an ordinary working woman pursuing freedom, winning her a César Award for Best Actress and symbolizing a turning point in gender consciousness. As SAUTET concluded: "Things never happen the way we expect. That is the subject of all my films."

|More from KFF|